Ever since femtosecond lasers were first introduced into refractive surgery, the ultimate goal has been to create an intrastromal lenticule that can then be removed in one piece manually, thereby circumventing the need for incremental photoablation by an excimer laser. This was achieved in 2005, presented at the American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO) meeting in Las Vegas in 2006, and published in 2008 with the Femtosecond Lenticule Extraction procedure (FLEx) in which a lenticule was manually removed after lifting a flap,1 11 years after this had first been demonstrated in rabbit eyes with a picosecond laser.2 Following the successful implementation of FLEx, a new procedure called small incision lenticule extraction (SMILE) was developed; an all-femtosecond laser, keyhole, flapless procedure that is in the process of revolutionizing corneal refractive surgery and realizing Jose Ignacio Barraquer’s original concept of keratomileusis.3,4

The SMILE procedure is gaining popularity following the results of the first prospective trials5–7 and more recent reports that have demonstrated that the visual and refractive outcome is similar to laser in situ keratomileusis (LASIK),8–18 and there have now been over 140,000 procedures performed worldwide with more than 300 surgeons regularly doing SMILE. The feasibility of the procedure has been proved by studies on the surface quality of the lenticules,19,20 wound healing and inflammation,21–23 and the accuracy of the lenticule thickness parameters have been verified using very-high-frequency digital ultrasound24,25 and optical coherence tomography (OCT).26–29

The safety has also been demonstrated to be similar to LASIK30 and our recent publication has shown that there are no concerns in treating patients with SMILE for low myopia.17

In terms of safety, SMILE also brings two advantages over LASIK, relevant to the most common complication: dry eye, and the most serious complication: ectasia. Both of these advantages stem from the minimally invasive pocket incision nature of the procedure as this results in maximal retention of anterior corneal innervational as well as structural integrity.

It was expected that there would be less postoperative dry eye after SMILE. While the trunk nerves that ascend into the epithelial layer within the diameter of the cap will continue to be severed in SMILE, those that ascend outside the cap diameter, or that are anterior to the cap interface will be spared. A number of studies have demonstrated a lower reduction and faster recovery of corneal sensitivity after SMILE than LASIK,31–39 with recovery to baseline after 3–6 months after SMILE compared with 6–12 months after LASIK. Some studies have also used confocal microscopy to demonstrate a lower decrease in sub-basal nerve fiber density after SMILE than LASIK.34,38,40

The other major advantage of SMILE is the biomechanical profile as the anterior stroma above the lenticule remains uncut (except in the location of the small incision), unlike in LASIK where anterior stromal lamellae are severed by the creation of the flap. It has been shown that the vertical sidecut of a flap is responsible for almost all of the change in strain due to LASIK flap creation.41 It has also been shown that the anterior corneal stroma is the strongest part of the stroma,42–45 due to the greater interconnectivity of collagen fibers in the anterior stroma compared with the posterior stroma where the collagen fibers lie in parallel to each other.46 Therefore, SMILE must leave the cornea with greater biomechanical strength than LASIK for the same amount of vision-correcting tissue removal. Not surprisingly, therefore, using a mathematical model based on the nonlinearity of tensile strength through the stroma, we have shown that SMILE leaves greater biomechanical strength even than photorefractive keratectomy (PRK) for the same amount of vision correcting tissue removal, as PRK involves ablating within the strongest anterior stroma.47 Surgeons are accustomed to calculating the residual stromal thickness in LASIK as the amount of stromal tissue left under the flap, and therefore the first instinct is to apply this rule to SMILE. However, for the reasons given above, the actual residual stromal thickness in SMILE should be calculated as the total uncut stroma (i.e., the stroma above and below the lenticule). This biomechanically allows for much higher corrections to be achieved by SMILE than either LASIK or PRK.

Efforts to measure the biomechanical difference have been mixed, however, this is probably due to the difficulty of measuring this in vivo. Out of five studies where the ocular response analyzer (Reichert Inc., Depew, NY) was used, two contralateral eye studies reported that corneal hysteresis (CH) and corneal resistance factor (CRF) were slightly greater after SMILE than LASIK,48,49 while three other studies reported no difference in either CH or CRF between the SMILE and LASIK groups.27,50,51 However, it is likely that CH and CRF are not ideal parameters for measuring corneal biomechanics given that many studies show no change in CH and CRF after crosslinking.52 Similar results have been reported using the CorVis ST tonometer (Oculus Optikgeräte GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany) with two studies finding no difference between SMILE and LASIK groups.53,54 Meanwhile, Mastropasqua et al.55 showed that after an initial increase, as expected due to tissue removal, the CorVis measurements were stable over the 3-month follow-up period.

Other evidence for biomechanical differences is that there is less induction of spherical aberration after SMILE compared with LASIK. In a recent study, we found that SMILE, though minimally aspheric, produced similar spherical aberration induction to the highly aspherically optimized laser blended vision profile.56 However, as the ablation depth was lower for SMILE, the optical zone could be increased meaning that less spherical aberration was induced for equivalent tissue removal, thus improving the optical quality for the patient. These results are similar to other published studies: two studies have shown that there are fewer aberrations induced by SMILE than LASIK,13,14 and one study showed that induction of aberrations was similar.12

The main disadvantage of SMILE currently is the slightly slower visual recovery experienced by some patients compared with LASIK: the day 1 visual acuity is on average slightly lower than LASIK.8 However, significant improvements have been made in this area by using different energy and spot spacing settings57 and the difference is now more like one or two lines difference in uncorrected distance visual acuity on postop day 1, equalizing by 2–3 weeks postoperatively.

One study described microdistortions in Bowman’s layer after SMILE58 identified by OCT, but with no clinically significant corneal striae at the slit-lamp. However, these microdistortions did not have an impact on visual acuity or quality. We have studied these central microdistortions and found that they can be minimized by appropriate centrifugal cap distension immediately at the end of the procedure to distribute redundant cap to the periphery.

Another aspect of SMILE that was thought to be a factor when compared with LASIK was that of enabling good centration, due to the absence of eye tracking. However studies have shown this to be in fact incorrect: the centration of SMILE is actually very straightforward and virtually takes care of itself. At the moment of contact between the individually calibrated curved contact glass and the cornea, a meniscus tear film appears, at which point the patient is able to see the fixation target very clearly—because the vergence of the fixation beam is focused according to the patient’s refraction. At this point, the surgeon instructs the patient to look directly at the green light and once in position, the corneal suction ports are activated to fixate the eye in this position. In this way, the patient essentially autocentrates the visual axis and hence the corneal vertex to the vertex of the contact glass, which is centered to the laser system and the center of the lenticule to be created. We confirm centration accuracy by comparing the relative positions of the fixation light to the pupil border to the printed placido eye image which we post directly above the microscope. Using this technique, centration of SMILE has been shown to be similar to that achieved with LASIK using a modern eye tracker.59,60

The ability to surgically extract an intact refractive lenticule of stromal tissue using the SMILE procedure has opened up a number of further possible applications. It has been demonstrated that refractive lenticules can be cryopreserved successfully for 1 month in rabbits61,62 and as long as 5–6 months in humans.63 It has been suggested that these lenticules could be re-implanted as a method for restoring tissue in ectatic corneas, or provide an opportunity for reversing the myopic correction in a patient progressing to presbyopia,61,62 and successful re-implantation was first demonstrated in rabbits.62

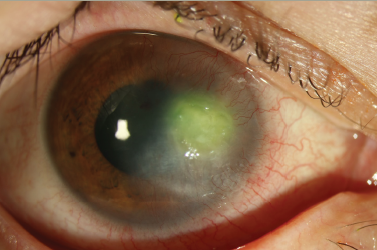

Alternatively, there is also the potential for implanting an allogenic lenticule obtained from a myopic donor patient into a hyperopic patient to correct the hyperopia, as originally proposed by Barraquer in 1980.4 The first case of this endokeratophakia procedure was performed in 201264 and a series of nine eyes has also been reported.63 Feasibility of the procedure has been demonstrated as corneal clarity was maintained, however, unintended posterior surface changes resulted in undercorrection of the effect.

Meanwhile, progress is being made on extending this technique to hyperopia with prospective studies currently running at the University of Marburg, Germany, under Professor Walter Sekundo using FLEx,65 and at the Tilganga Institute of Ophthalmology, Nepal, under Dr Kishore Pradhan and my group using SMILE,66 with encouraging results.

The evolution of SMILE, a flapless intrastromal keyhole keratomileusis procedure, has introduced a new, minimally invasive method for corneal refractive surgery. The visual and refractive outcomes of the procedure have been shown to be similar to LASIK, while there is increasing evidence for the benefits of SMILE over LASIK by leaving the anterior stroma intact including superior biomechanics and faster recovery of dry eye and corneal nerve reinnervation.

References

1. Sekundo W, Kunert K, Russmann C, et al., First efficacy and safety study of femtosecond lenticule extraction for the correction of myopia: six-month results, J Cataract Refract Surg, 2008;34:1513–20.

2. Ito M, Quantock AJ, Malhan S, et al., Picosecond laser in situ keratomileusis with a 1053-nm Nd:YLF laser, J Refract Surg, 1996;12:721–8.

3. Barraquer JI, Queratomileusis para la correccion de la miopia, Arch Soc Am Oftal Optom, 1964;5:81–7.

4. Barraquer JI, Queratomileusis y queratofakia, Bogota: Instituto Barraquer de America, 1980:342.

5. Sekundo W, Kunert KS, Blum M, Small incision corneal refractive surgery using the small incision lenticule extraction (SMILE) procedure for the correction of myopia and myopic astigmatism: results of a 6 month prospective study, Br J Ophthalmol, 2011;95:335–9.

6. Shah R, Shah S, Sengupta S, Results of small incision lenticule extraction: All-in-one femtosecond laser refractive surgery, J Cataract Refract Surg, 2011;37:127–37.

7. Hjortdal JO, Vestergaard AH, Ivarsen A, et al., Predictors for the outcome of small-incision lenticule extraction for myopia, J Refract Surg, 2012;28:865–71.

8. Vestergaard A, Ivarsen AR, Asp S, Hjortdal JO, Smallincision lenticule extraction for moderate to high myopia: Predictability, safety, and patient satisfaction, J Cataract Refract Surg, 2012;38:2003–10.

9. Wang Y, Bao XL, Tang X, et al., [Clinical study of femtosecond laser corneal small incision lenticule extraction for correction of myopia and myopic astigmatism], Zhonghua Yan Ke Za Zhi, 2013;49:292–8.

10. Kamiya K, Shimizu K, Igarashi A, Kobashi H, Visual and refractive outcomes of femtosecond lenticule extraction and small-incision lenticule extraction for myopia, Am J Ophthalmol, 2014;157:128–34 e122.

11. Sekundo W, Gertnere J, Bertelmann T, Solomatin I, One-year refractive results, contrast sensitivity, high-order aberrations and complications after myopic small-incision lenticule extraction (ReLEx SMILE), Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol, 2014;252:837–43.

12. Agca A, Demirok A, Cankaya KI, et al., Comparison of visual acuity and higher-order aberrations after femtosecond lenticule extraction and small-incision lenticule extraction, Cont Lens Anterior Eye, 2014;37:292–6.

13. Lin F, Xu Y, Yang Y, Comparison of the visual results after SMILE and femtosecond laser-assisted LASIK for myopia, J Refract Surg, 2014;30:248–54.

14. Ganesh S, Gupta R, Comparison of visual and refractive outcomes following femtosecond laser- assisted lasik with smile in patients with myopia or myopic astigmatism, J Refract Surg, 2014;30:590–6.

15. Kunert KS, Melle J, Sekundo W, et al., [One-year results of Small incision lenticule extraction (SMILE) in myopia], Klin Monbl Augenheilkd, 2015;232:67–71.

16. Kim JR, Hwang HB, Mun SJ, et al., Efficacy, predictability, and safety of small incision lenticule extraction: 6-months prospective cohort study, BMC Ophthalmol, 2014;14:117.

17. Reinstein DZ, Carp GI, Archer TJ, Gobbe M, Outcomes of small incision lenticule extraction (SMILE) in low myopia, J Refract Surg, 2014;30:812–8.

18. Ang M, Mehta JS, Chan C, et al., Refractive lenticule extraction: transition and comparison of 3 surgical techniques, J Cataract Refract Surg, 2014;40:1415–24.

19. Kunert KS, Blum M, Duncker GI, et al., Surface quality of human corneal lenticules after femtosecond laser surgery for myopia comparing different laser parameters, Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol, 2011;249:1417–24.

20. Ziebarth NM, Lorenzo MA, Chow J, et al., Surface quality of human corneal lenticules after SMILE assessed using environmental scanning electron microscopy, J Refract Surg, 2014;30:388–93.

21. Angunawela RI, Poh R, Chaurasia SS, et al., A mouse model of lamellar intrastromal femtosecond laser keratotomy: ultrastructural, inflammatory, and wound healing responses, Mol Vis, 2011;17:3005–12.

22. Riau AK, Angunawela RI, Chaurasia SS, et al., Early corneal wound healing and inflammatory responses after refractive lenticule extraction (ReLEx), Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 2011;52:6213–21.

23. Dong Z, Zhou X, Wu J, et al., Small incision lenticule extraction (SMILE) and femtosecond laser LASIK: comparison of corneal wound healing and inflammation, Br J Ophthalmol, 2014;98:263–9.

24. Reinstein DZ, Archer TJ, Gobbe M, Accuracy and reproducibility of cap thickness in small incision lenticule extraction, J Refract Surg, 2013;29:810–5.

25. Reinstein DZ, Archer TJ, Gobbe M, Lenticule thickness readout for small incision lenticule extraction compared to Artemis three-dimensional very high-frequency digital ultrasound stromal measurements, J Refract Surg, 2014;30:304–9.

26. Zhao J, Yao P, Li M, et al., The morphology of corneal cap and its relation to refractive outcomes in femtosecond laser small incision lenticule extraction (SMILE) with anterior segment optical coherence tomography observation, PLoS One, 2013;8:e70208.

27. Vestergaard AH, Grauslund J, Ivarsen AR, Hjortdal JO, Central corneal sublayer pachymetry and biomechanical properties after refractive femtosecond lenticule extraction, J Refract Surg, 2014;30:102–8.

28. Ozgurhan EB, Agca A, Bozkurt E, et al., Accuracy and precision of cap thickness in small incision lenticule extraction, Clin Ophthalmol, 2013;7:923–6.

29. Tay E, Li X, Chan C, et al., Refractive lenticule extraction flap and stromal bed morphology assessment with anterior segment optical coherence tomography, J Cataract Refract Surg, 2012;38:1544–51.

30. Ivarsen A, Asp S, Hjortdal J, Safety and complications of more than 1500 small-incision lenticule extraction procedures, Ophthalmology, 2014;121:822–8.

31. Reinstein DZ, Archer TJ, Gobbe M, Bartoli E, Corneal sensitivity after small incision lenticule extraction (SMILE), J Cataract Refract Surg, 2015 [In Press].

32. Wei S, Wang Y, Comparison of corneal sensitivity between FS-LASIK and femtosecond lenticule extraction (ReLEx flex) or small-incision lenticule extraction (ReLEx smile) for myopic eyes, Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol, 2013;251:1645–54.

33. Wei SS, Wang Y, Geng WL, et al., [Early outcomes of corneal sensitivity changes after small incision lenticule extraction and femtosecond lenticule extraction], Zhonghua Yan Ke Za Zhi, 2013;49:299–304.

34. Vestergaard AH, Gronbech KT, Grauslund J, et al., Subbasal nerve morphology, corneal sensation, and tear film evaluation after refractive femtosecond laser lenticule extraction, Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol, 2013;251:2591–600.

35. Demirok A, Ozgurhan EB, Agca A, et al., Corneal sensation after corneal refractive surgery with small incision lenticule extraction, Optom Vis Sci, 2013;90:1040–7.

36. Li M, Zhao J, Shen Y, et al., Comparison of dry eye and corneal sensitivity between small incision lenticule extraction and femtosecond LASIK for myopia, PLoS One, 2013;8:e77797.

37. Li M, Zhou Z, Shen Y, et al., Comparison of corneal sensation between small incision lenticule extraction (SMILE) and femtosecond laser-assisted LASIK for myopia, J Refract Surg, 2014;30:94–100.

38. Li M, Niu L, Qin B, et al., Confocal comparison of corneal reinnervation after small incision lenticule extraction (SMILE) and femtosecond laser in situ keratomileusis (FS-LASIK), PLoS One, 2013;8:e81435.

39. Gao S, Li S, Liu L, et al., Early changes in ocular surface and tear inflammatory mediators after small-incision lenticule extraction and femtosecond laser-assisted laser in situ keratomileusis, PLoS One, 2014;9:e107370.

40. Mohamed-Noriega K, Riau AK, Lwin NC, et al., Early corneal nerve damage and recovery following small incision lenticule extraction (SMILE) and laser in situ keratomileusis (LASIK), Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 2014;55:1823–34.

41. Knox Cartwright NE, Tyrer JR, Jaycock PD, Marshall J, Effects of variation in depth and side cut angulations in LASIK and thinflap LASIK using a femtosecond laser: A biomechanical study, J Refract Surg, 2012;28:419–25.

42. Randleman JB, Dawson DG, Grossniklaus HE, et al., Depthdependent cohesive tensile strength in human donor corneas: implications for refractive surgery, J Refract Surg, 2008;24:S85–9.

43. Scarcelli G, Pineda R, Yun SH, Brillouin optical microscopy for corneal biomechanics, Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 2012;53:185–90.

44. Petsche SJ, Chernyak D, Martiz J, et al., Depth-dependent transverse shear properties of the human corneal stroma, Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 2012;53:873–80.

45. Kohlhaas M, Spoerl E, Schilde T, et al., Biomechanical evidence of the distribution of cross-links in corneas treated with riboflavin and ultraviolet A light, J Cataract Refract Surg, 2006;32:279–83.

46. Winkler M, Shoa G, Xie Y, et al., Three-dimensional distribution of transverse collagen fibers in the anterior human corneal stroma, Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 2013;54:7293–301.

47. Reinstein DZ, Archer TJ, Randleman JB, Mathematical model to compare the relative tensile strength of the cornea after PRK, LASIK, and small incision lenticule extraction, J Refract Surg, 2013;29:454–60.

48. Wu D, Wang Y, Zhang L, et al., Corneal biomechanical effects: Small-incision lenticule extraction versus femtosecond laserassisted laser in situ keratomileusis, J Cataract Refract Surg, 2014;40:954–62.

49. Wang D, Liu M, Chen Y, et al., Differences in the corneal biomechanical changes after SMILE and LASIK, J Refract Surg, 2014;30:702–7.

50. Agca A, Ozgurhan EB, Demirok A, et al., Comparison of corneal hysteresis and corneal resistance factor after small incision lenticule extraction and femtosecond laser-assisted LASIK: a prospective fellow eye study, Cont Lens Anterior Eye, 2014;37:77–80.

51. Kamiya K, Shimizu K, Igarashi A, et al., Intraindividual comparison of changes in corneal biomechanical parameters after femtosecond lenticule extraction and small-incision lenticule extraction, J Cataract Refract Surg, 2014;40:963–70.

52. Goldich Y, Barkana Y, Morad Y, et al., Can we measure corneal biomechanical changes after collagen crosslinking in eyes with keratoconus?—a pilot study, Cornea, 2009;28:498–502.

53. Pedersen IB, Bak-Nielsen S, Vestergaard AH, et al., Corneal biomechanical properties after LASIK, ReLEx flex, and ReLEx smile by Scheimpflug-based dynamic tonometry, Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol, 2014;252:1329–35.

54. Shen Y, Chen Z, Knorz MC, et al., Comparison of corneal deformation parameters after SMILE, LASEK, and femtosecond laser-assisted LASIK, J Refract Surg, 2014;30:310–8.

55. Mastropasqua L, Calienno R, Lanzini M, et al., Evaluation of corneal biomechanical properties modification after small incision lenticule extraction using scheimpflug-based noncontact tonometer, Biomed Res Int, 2014;2014:290619.

56. Reinstein DZ, Archer TJ, Gobbe M, Spherical aberration change as a function of pupil size: a comparison between small incision lenticule extraction [SMILE] and non-linear aspheric LASIK in moderate to high myopia, ARVO, Fort Lauderdale, US, 2012.

57. Shah R, Shah S, Effect of scanning patterns on the results of femtosecond laser lenticule extraction refractive surgery, J Cataract Refract Surg, 2011;37:1636–47.

58. Yao P, Zhao J, Li M, et al., Microdistortions in Bowman’s layer following femtosecond laser small incision lenticule extraction observed by Fourier-Domain OCT, J Refract Surg, 2013;29:668–74.

59. Gobbe M, Reinstein DZ, Carp GI, et al., Optical zone centration comparison between SMILE and LASIK. ARVO 2015. Denver, CO, US, 2015.

60. Lazaridis A, Droutsas K, Sekundo W, Topographic analysis of the centration of the treatment zone after SMILE for myopia and comparison to FS-LASIK: Subjective versus objective alignment, J Refract Surg, 2014;30:680–6.

61. Mohamed-Noriega K, Toh KP, Poh R, et al., Cornea lenticule viability and structural integrity after refractive lenticule extraction (ReLEx) and cryopreservation, Mol Vis, 2011;17:3437–49.

62. Angunawela RI, Riau AK, Chaurasia SS, et al., Refractive lenticule re-implantation after myopic ReLEx: a feasibility study of stromal restoration after refractive surgery in a rabbit model, Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 2012;53:4975–85.

63. Ganesh S, Brar S, Rao PA, Cryopreservation of extracted corneal lenticules after small incision lenticule extraction for potential use in human subjects, Cornea, 2014;33:1355–62.

64. Pradhan KR, Reinstein DZ, Carp GI, et al., Femtosecond laserassisted keyhole endokeratophakia: Correction of hyperopia by implantation of an allogeneic lenticule obtained by SMILE from a myopic donor, J Refract Surg, 2013;29:777–82.

65. Sekundo W, Blum M, ReLEx Flex for hyperopia. European Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery Annual Meeting. London, UK, 2014.

66. Reinstein DZ, Pradhan KR, Carp GI, et al., Preliminary evaluation of hyperopic SMILE in amblyopic eyes. ARVO 2015. Denver, CO, USA, 2015.