The prevalence of both dry eye disease and sleep apnoea has steadily increased in the USA.1 Importantly, new research reveals the need for multispecialty collaboration based on evidence that patients may be at risk for eye irritation secondary to airflow from mask leakage or retrograde nasolacrimal air escape.2

Sleep apnoea and ocular disorders

Sleep apnoea is a partial to complete upper-airway collapse with decreased airflow causing oxygen desaturation and/or arousal from sleep.3 Approximately 13–14% of men and 5–6% of women in the USA have sleep apnoea, and these figures have increased substantially in recent years.1 Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) ventilation or other nasal mask therapy (NMT) devices are the widely recommended treatment for obstructive sleep apnoea.4 CPAP use is highly beneficial, with patients experiencing significant improvements in several quality-of-life measures after 6 months of treatment.5 For example, patients report improved daily functioning, emotional functioning and social interaction, along with decreased daytime fatigue.5 However, many patients using CPAP or NMT develop secondary ocular disorders.4 For example, a recent investigation by Muhafiz et al. evaluated the effect of obstructive sleep apnoea-hypopnoea syndrome on the meibomian glands, ocular surface and tear parameters.6 They found greater meibomian gland loss in both the upper and lower eyelids of the sleep apnea group compared with the control group, as well as a statistically significant correlation between the severity of sleep apnoea and the total meibomian gland loss percentage.6

Earlier research supports these findings, with one study in particular revealing that approximately 50% of patients with sleep apnoea exhibit abnormal eye findings.7 The primary cause of the ocular issues is believed to be mask-edge leakage, resulting in surface irritation, tear-film abnormality, lid laxity and floppy eyelid syndrome.8

Sleep apnoea treatment and dry eye disease

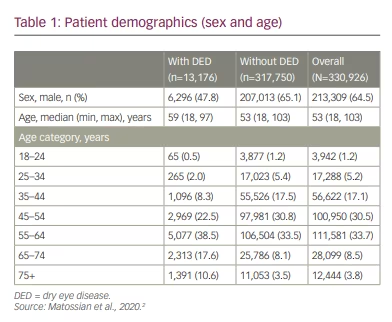

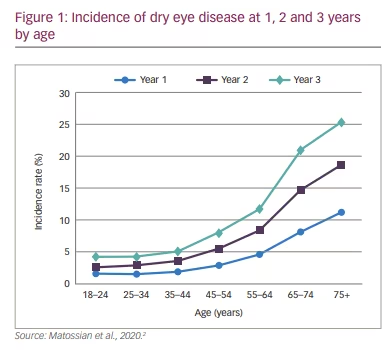

A staggering 6.8% of the US population (approximately 16.4 million adults) has received a dry eye disease diagnosis.9 An additional 2.5% are estimated to have dry eye disease in the absence of a clinical diagnosis.9 Adding to earlier research on general ocular disease in CPAP users, a recent retrospective descriptive analysis provides further information on the prevalence and incidence of dry eye disease among patients using CPAP or other NMT devices to treat sleep apnoea.2 Here, researchers found clear evidence that, compared with the incidence of dry eye disease in the general US adult population, the incidence of dry eye disease was higher in patients who used CPAP or a NMT device, particularly starting in the second year of use. Furthermore, the incidence of dry eye disease increased based on the length of time the CPAP device was used.2 Additional descriptive statistics are listed in Table 1.

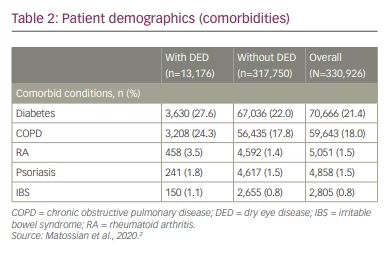

In the study, most patients (65%) were male, with a median age of 53 years. The investigation revealed that the 1-year, 2-year and 3-year incidence rates of dry eye disease in CPAP patients were 4.0%, 7.3% and 10.3%, respectively. Dry eye disease incidence increased similarly over time regardless of index year. Details are reported in Figure 1. Briefly, incidence increased with age, with 1-year incidence ranging from 1.6% in patients 18–24 years of age to 11.2% in patients ≥75 years of age. The 1-year incidence of dry eye disease was higher in women compared with men (5.8% versus 3.0%). Furthermore, the incidence of dry eye disease was higher among patients with comorbid metabolic or inflammatory conditions, as illustrated in Table 2. One-year incidence rates by comorbidity were: psoriasis, 9.1%; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, 5.4%; irritable bowel syndrome, 5.3%; diabetes, 5.1%; rheumatoid arthritis, 5.0%.2

This study is particularly meaningful due to the large sample size (N=330,926 patients). Investigators used data from the IBM MarketScan® Commercial and Medicare Supplemental Databases, which contain inpatient, outpatient and outpatient prescription-drug experience of several million patients covered under a variety of fee-for-service, capitated health plans and individuals with Medicare supplemental insurance paid by employers. The 330,926 patients who were included in the study had no diagnosis of dry eye disease prior to their first CPAP or NMT device claim.

Implications

In conclusion, patients will be best served if eye care practitioners and sleep specialists collaborate to provide comprehensive treatment. Due to the essential benefits of sleep apnoea therapy,4 solutions must be found to properly co-manage these patients. This begins by identifying patients who use CPAP and querying them about eye irritation. In short, ophthalmologists, optometrists and other eye care specialists should ask their patients about sleep apnoea and CPAP use, and collaborate with sleep specialists.

This review of the available research showing the correlation between CPAP use and dry eye disease is valuable in its own right, but looking ahead, practitioners in both specialties would benefit from greater collaboration into the mechanisms through which these presentations overlap. Currently, these details are scarce and therefore warrant

further investigation.